Understanding the Hierarchy of Controls through a Pandemic

As appearing in Professional Safety Journal and assp.org. May 2020.

Like many safety professionals, I tend to view the world through the lens of OSH concepts. I am proud of my keen and constant eye, but my kids have a different opinion of this skill. According to my children, the day I informed the golf course of a deep, uncovered hole on the putting green, they were terribly embarrassed.

Even worse was the day I surprised a store owner with information that an employee was improperly using a ladder on the grounds. And, apparently, I was “exhausting” during a recent trip abroad, pointing out every safety concern observed. “Stop, Mom!” they pleaded, to which I said, “I can’t help it.”

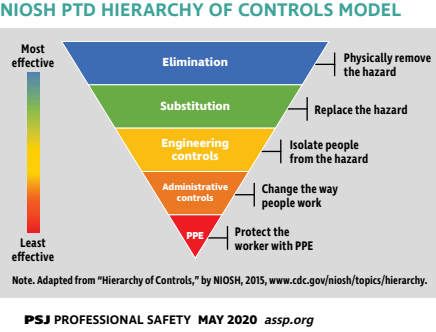

That is what led me to consider the NIOSH hierarchy of controls (Figure 1) in relation to the crisis with COVID-19. The hierarchy of controls is a foundational concept for methodically solving OSH challenges. This methodology consists of five ways of mitigating or eliminating a hazard that are ranked in order of effectiveness and, therefore, preference.

Let’s review the components of the hierarchy of controls and consider how they apply to a pandemic, progressing through each control from most to least effective since this is the order of consideration.

Elimination

The first and most effective control is elimination. Think of elimination as physically removing the hazard. How can we eliminate this deadly virus? It is possible to eradicate viruses. By denying access to host cells, the virus will be unable to replicate. Denying access comes in the form of effective vaccinations and transmission prevention. Eventually, extinction of the virus will occur. Virus eradication is complicated and not a short-term solution. According to Russell (2011), this has only been accomplished with two viruses to date: smallpox (1979) and rinderpest virus (2011). Although hazard elimination is the first choice, it may not be possible, may not be a timely solution or may be cost prohibitive. Currently, in the case of COVID-19, elimination (i.e., development of a vaccination) is underway.

Substitution

Second on the hierarchy of controls is substitution: replacing a given hazard with something less hazardous. So, for example, a more lethal virus would be replaced with a less lethal virus. Administering a drug that interferes with the virus’s ability to replicate once a person is infected is, in effect, making a more lethal virus into a less lethal one. This is possible but research (competent people, time and money allowing) is needed to identify the correct drug. Substitution work to mitigate the potency of this virus is underway.

Engineering Controls

Next is implementation of engineering controls. Essentially, this involves isolating people from the hazard or placing a barrier between them. A physical barrier, such as a glass transaction window with a speak-thru device as is used at a bank drive-up window, provides protection from viral exposure and is a form of engineering control. For those doing research on this virus, work in a ventilation hood is an example of protection through use of an engineering control. Engineering controls generally take time to invent, create, fabricate, produce and implement. For this reason, we need the next two controls. There also may be situations in which administrative controls and PPE are an appropriate supplement to the higher-level controls.

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls, or changing the way people work or act, is next on the hierarchy of controls. Changes in policy or procedures aimed at reducing or minimizing hazard exposure define an administrative control. Personal hygiene practices such as frequent handwashing with the appropriate soap and for the necessary amount of time, isolation of people, limiting the size of gatherings, and keeping a 6-ft separation between people when in groups are all examples of administrative controls. However, administrative controls have a distinct downside. Compliance is needed for this type of control to be effective and human beings are rarely perfect at compliance.

Administrative controls have their place and are needed in the hierarchy of controls. The more effective controls may not be easily implemented or put in place in a timely manner. Administrative controls can be a temporary solution, bridging the gap until more effective controls can be employed.

PPE

Last on the hierarchy of controls, and considered least effective is PPE. This includes items such as gloves, masks and protective clothing that provide a barrier between the person and the hazard. Effectiveness of this control requires that the right equipment is used, it must not be damaged and workers must remember to wear it. Training on the proper use and limitations of the PPE is also needed. Lack of available PPE where and when it is needed may also be an issue. For all of these reasons, PPE is the least effective control method, yet it has been a major focus during the pandemic. PPE can be implemented quickly (if equipment is available) and is a solution for buying down risk while waiting for more effective controls to come to fruition.

Conclusion

The hierarchy of controls is an effective model for working toward mitigation and elimination of hazards, including those faced during a pandemic. Methodically working through each element of the hierarchy of controls (elimination; substitution; engineering controls; administrative controls; PPE) and creatively applying these controls to the problem can achieve successful elimination of hazards.